A residential street in Aix. Cezanne lived in this house at one time.

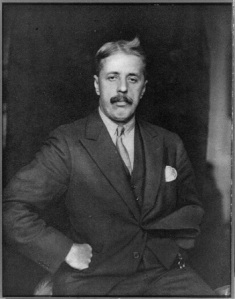

Emile Zola was born in Aix-en-Provence, Paris*, but as a boy he lived in Aix-en-Provence, to which he gives the name of Plassans in his series of Rougon-Macquart novels. Aix is an old town, founded by the Romans with houses built of the local stone.

* LH edit: Thanks to a query from David Wilson, (see comments below) I have edited Zola’s birthplace. He was born in Paris, the family moved to Aix-en-Provence when Émile was three and four years later after his died, his mother took the family back to Paris.

The now-abandoned quarry from which the stone came. Zola and Cezanne undoubtedly played here as boys.

Cezanne’s paining of the quarry.

In Zola’s time Aix was still surrounded by walls with gates that could be locked at night, as described in The Fortune of the Rougons.

Until 1853 these opening were fitted out with huge wooden two-leaved gates, arched at the top and reinforced with iron bars. These gates were double-locked at eleven o’clock in summer and ten o’clock in winter. The town having thus shots its bolts like a timid girl, went quietly to sleep.

The walls were gone when I visited Aix less than 10 years ago, but the present encircling boulevards follow the lines they once established.

The walls were gone when I visited Aix less than 10 years ago, but the present encircling boulevards follow the lines they once established.

The former gate, the Porte des Augustins, has been replaced by La Ronde, a traffic circle in the center of which is a handsome fountain. You also find the Tourist Office there, a very appropriate location since one of Aix’s principal occupations now is tourism.

The former gate, the Porte des Augustins, has been replaced by La Ronde, a traffic circle in the center of which is a handsome fountain. You also find the Tourist Office there, a very appropriate location since one of Aix’s principal occupations now is tourism.

The Cours Mirabeau, identified as Cours Sauvaire in Zola’s Plassans, begins at La Ronde and has not moved from Zola’s time. The street itself is wide and shaded, and you can still find a café where Cezanne and Zola once enjoyed the local scene. The Cours divides two sections of the town, a community where each group knew and accepted its place.

It is only once a week, and when the weather is good, that the three districts of Plassans come face to face. The whole town repairs to the Cours Sauvaire on Sunday after vespers; even the nobility venture there.

Cours Mirabeau today. Note restricted automobile traffic — plenty of room for strollers then and now.

This cafe on the Cours Mirabeau was also popular in Zola’s day.

The contemporary map shown above is one that is given to tourists for a self-guided walking tour of sites associated with Paul Cezanne, currently Aix’s favorite son. Zola is rarely mentioned at the tourist office, except in connection with Cezanne. The two were boyhood friends in Aix, both left it for Paris. Zola stayed in Paris, but Cezanne returned to Aix. They remained in touch but had a falling out when Cezanne saw himself portrayed unflatteringly in Zola’s novel L’Oeuvre.

Zola Dam, 100 years ago.

The citizens of Plassans from Zola’s day and the citizens of Aix today have, however, good reason to honor the Zola family. Zola’s father, Francois Zola, designed and built an important dam to assure a supply of water to the town.

Zola Dam today. It is still in use.

In Provence today, the countryside relies on a complex system of dams, canals and irrigation ditches to provide water in a semi-arid climate. When Francois Zola died prematurely his family felt cheated of the rewards to which they felt entitled for his work. This bitterness affects Zola’s descriptions of Plassans as a small-minded, conservative place.

Irrigation ditch in the Provence countryside.

Cezanne’s Studio, 1902

Within Aix, walking in the narrow street of the old parts of town – the area which was once within the medieval walls – one has little sense of the surrounding countryside. Both Zola and Cezanne knew it well however, and one finds it in the night wanderings of Silvere and Miette in The Fortunes of the Rougons. Walk out of central Aix and climb the hill to Paul Cezanne’s old studio, and you can see something of what they knew. The studio itself, built in Cezanne’s mature years of somewhat greater prosperity was once isolated on a hillside.

It is lonely no more, as tourist line up to see where the artist once worked.

Cezanne’s Studio on a rainy afternoon.

Best of all, look out from the location.

View from the street outside Cezanne’s Studio.

The view reminds me of the anxious night Rougon spent on the terrace looking for signs of the insurrectionists.

At the end of the garden there was a terrace that overlooked the plain; a large section of the ramparts had collapsed at that point, giving an unimpeded view…. In the distance, in the valley of the Viorne, across the vast hollow that stretched westwards between the chain of the Garrigues and the mountains of the Scille, the moonlight was streaming down like a river of pale light. The clumps of trees and the dark rocks looked, here and there, like islets and tongues of land emerging from a luminous sea. And corresponding to the bends of the Viorne, it was possible to see patches and slithers of the river….

Bridge over the “Viorne.” Zola painted a picture of this bridge so it must have been there in Zola’s day.

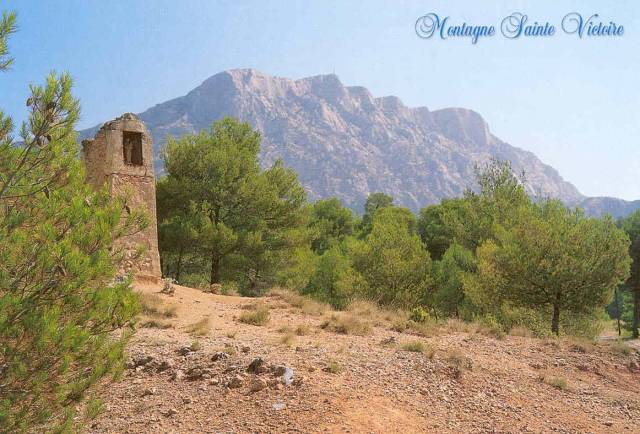

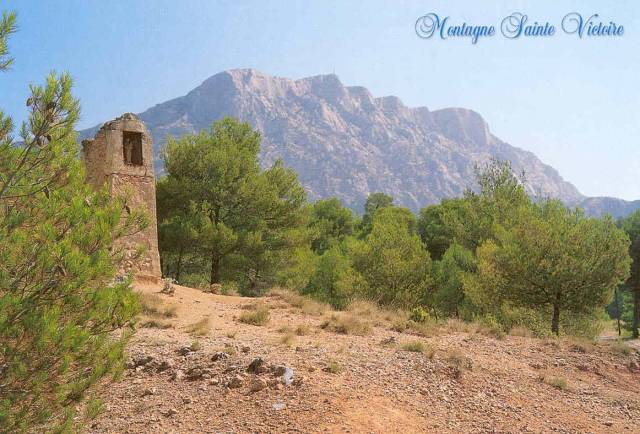

The stony ridge in the distance is, of course, Mt. Ste. Victoire, the subject of many of Cezanne’s landscapes.

We took a van tour which circled the mountain and found it fascinating. The ridge is so placed that one can never see the entire thing at once. It is long, very steep in places, and presents a different shape when seen from each side and angle. Like the grand canyon, the play of light on the rocks brings the mountain forms nearer during some parts of the day and softens and distances them at other times. When Cezanne returned to Aix from Paris, he found a subject worthy of his skill and could spend the rest of his life interpreting the local scene.

Mt. Ste. Victoire by Cezanne — one of many versions of the mountain and the surrounding plain. It looks much the same today, including the stone viaduct.

Zola, on the other hand, could not find in his Plassans a wide enough canvas for his artistic dream. In L’Oeuvre, the writer lays out a comprehensive program of work and systematically applies himself to bringing it forth. It is not always appreciated but he has confidence in its value. This is very much what Zola did when he wrote his Rougon-Macquart novels. He made a plan and worked at it, book after book, year after year.

Zola’s fictional artist is not appreciated either. He stays in Paris, where he creates and destroys, creates and destroys in an attempt to make something so perfect that it must be acknowledged. This is the characterization which so disturbed Cezanne that he never spoke to Zola again. Since visiting Aix I think the two men were more alike that Zola acknowledged. Both worked in accordance with how they saw the world. Zola could not create as he wanted to within Plassans. He needed a wider scene and found it in Paris. Cezanne did not hang himself like the artist in L’Oeuvre. Instead, he left Paris to live and exercise his imagination in Aix, where his landscapes look out from the town, not back towards it.

Today Plassans/Aix is a short bus ride from the Marseilles airport. Aix in the 21st century is a modern city with a well-preserved older center. I was a tourist there a few years ago, walking in the town and enjoying the landscapes. The experience gave me a strong sense of the physical environment in which Zola lived during his formative years. The spirit of the place seems quite different from the Plassans of Zola. Aix is open, hospitable to tourists, and has a large population of foreign students, adding to a cosmopolitan atmosphere you do not find in the Rougon-Macquart novels.

On-line commentators have now discovered creative disruption – or, more aggressively, creative destruction – the price of progress as new technology and methods disrupt the comfortable status quo. The innovation is not usually the result of customer demand, but of imaginative foresight by some entrepreneur. As Henry Ford is said to have said, “If I asked the customer what he wanted, he would have said ‘a faster horse.’”

On-line commentators have now discovered creative disruption – or, more aggressively, creative destruction – the price of progress as new technology and methods disrupt the comfortable status quo. The innovation is not usually the result of customer demand, but of imaginative foresight by some entrepreneur. As Henry Ford is said to have said, “If I asked the customer what he wanted, he would have said ‘a faster horse.’”