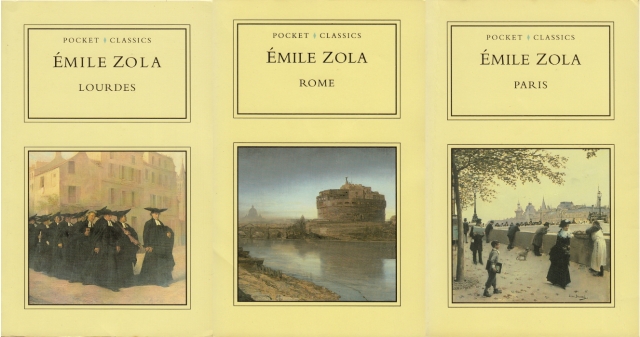

Paris is the last volume in the Three Cities trilogy and was first published in 1898. After the struggle I had with the previous volume, Rome, (see here and here) I did wonder if I would ever finish the trilogy; but I have. Even the first volume in the series, Lourdes, was a bit of a struggle. The main character throughout the series is the Abbé Pierre Froment, a priest who no longer retains his faith, and although Zola makes us sympathise with Froment’s predicament we know right from the start that he will end up leaving the church; it just takes so bloody long for it to happen. The whole series is seriously flawed, in my opinion, Lourdes would have worked better as a piece of journalism, Rome should have been abandoned completely, although a short story could possibly have been salvaged from it, and Paris, which was the best of the three, would still have worked better without Pierre’s struggle with his faith.

Paris opens with Pierre agreeing to take some alms from Abbé Rose to a former house painter, called Laveuve, who is on the verge of starving to death. Abbé Rose is being watched by his superiors as his persistent alms-giving is starting to annoy the church hierarchy. Pierre agrees to take the few francs to the man and visits Laveuve in his working-class slum. Pierre witnesses many scenes of poverty which Zola describes ruthlessly. Pierre enquires with a family as to the whereabouts of Laveuve, whom they know as ‘The Philosopher’. Pierre eventually locates him in a nearby hovel.

Here, on a human face, appeared all the ruin following upon hopeless labour. Laveuve’s unkempt beard straggled over his features, suggesting an old horse that is no longer cropped; his toothless jaws were quite askew, his eyes were vitreous, and his nose seemed to plunge into his mouth. But above all else one noticed his resemblance to some beast of burden, deformed by hard toil, lamed, worn to death, and now only good for the knackers.

Pierre not only delivers the alms from Rose but he also spends the rest of the day trying to get Laveuve admitted into the Asylum of the Invalids of Labour by using his connections with the wealthy people on the board of the organisation. Zola here presents the high-society of Paris, particularly the Duvillard’s family and friends; the Baron Duvillard is a banker involved in an African Railway scheme and his wife, Eve, does at least want to help Pierre. But he’s passed around from person to person, none of whom are willing to help him directly. In the end all his efforts are in vain as Leveuve dies before any decision can be made. He is disgusted with himself that he had allowed his hopes to rise once again, to hope that he could actually help people with charity, and as a result his doubts return.

He had ceased to believe in the efficacy of alms; it was not sufficient that one should be charitable, henceforth one must be just. Given justice, indeed, horrid misery would disappear, and no such thing as charity would be needed.

Pierre is then witness to an act of terrorism as he notices a man, Salvat, whom he had seen when visiting Laveuve, meet Pierre’s brother, Guillaume. Salvat walks away to the Duvillard’s mansion, followed by Guillaume, who is followed by Pierre. Pierre watches Salvat enter a doorway and is soon seen running from the building; Guillaume enters the building and there follows an explosion. Pierre helps his injured brother get away and lets him stay at his house to recuperate. The only casualty of the bomb is a young servant girl.

Pierre and Guillaume, who had been estranged, now become better acquainted and Pierre gets to know both Guillaume’s family and his revolutionary friends. Guillaume is a chemist who had been working on a new explosive and Salvat had managed to pilfer some of this when he was working briefly for Guillaume. The rest of the novel now concentrates on Pierre’s complete disassociation with the church and his appreciation of Guillaume’s scientific and atheistic outlook on life. Pierre is completely astonished and then smitten by Guillaume’s fiancée, Marie, who seems to embody the best of this new, more open, outlook to life. Now that Pierre has lost his faith in God he seems to find a new faith in some sort of scientific positivism, whereby all the problems of the world are going to be solved by socialism, science and work. This was no doubt close to Zola’s personal views but it certainly seems to be highly unrealistic to a modern reader. I wonder how the contemporary reader would have found these arguments? It is strange that all the political talk about socialism and anarchism concentrates on Saint-Simon, Fourier, Proudhon et al. rather than Marx, Engels, Bakunin et al.; it’s almost as if a hundred years of political thought meant nothing to Zola.

There is a lot more in this novel as well; there’s the manhunt of Salvat as well as his public execution; the threat of terrorism; there’s Zola’s look at bourgeois society and its decadence at the end of the nineteenth century by portraying political, financial and moral corruption; there’s the joys of cycling (for men AND women); the joys of marriage and fatherhood. Unusually for Zola this novel has a very positive, almost utopian, ending, predicting the downfall of Catholicism and the rise of Science and Justice.

Therein lies the new hope—Justice, after eighteen hundred years of impotent Charity. Ah! in a thousand years from now, when Catholicism will be naught but a very ancient superstition of the past, how amazed men will be to think that their ancestors were able to endure that religion of torture and nihility!

I wonder what Zola would have made of the world today?

The novel ends with the whole family looking out over a Paris bathed in golden light from the setting sun. Marie holds up her son, Jean, to look at the sight, promising him that he’s going to reap the benefits that Science and Justice are going to bring. Jean would be aged sixteen in 1914.

This was cross-posted on my blog Intermittencies of the Mind.