Zola is famous for his novels, especially the excellent Rougon-Macquart series, so I was a little bit nervous approaching a book of his short stories. Would Zola continue to impress or would he falter in this format? In my experience novelists aren’t always good short story writers and vice versa; they seem to be quite separate skills. Well, the answer is that he did not fail, and this collection is, with a few exceptions, an impressive collection of stories that is as good as anything I’ve read by him so far. They are similar in style and quality to the best of Chekhov’s short stories.

The stories included in this volume range from a few early stories to one he wrote in 1899 during his exile in England but the bulk, and the best, of the stories were written between 1877 and 1880 for the Russian periodical Vestnik Evropy or European Messenger. More details of the stories can be found on this earlier post.

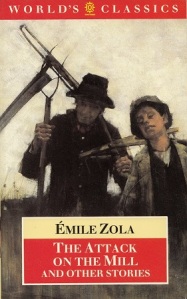

This ‘Oxford University Press’ (OUP) collection was published in 1984 and all the stories were translated by Douglas Parmeé. More recently it has been re-issued by ‘Oneworld’ as ‘Dead Men Tell No Tales and Other Stories’. In that book it mentions that the collection was first published in 1969 by OUP but no mention of this is made in my OUP version; the only copyright information is for 1984. There are loads of notes at the back which includes lots of information on each story such as original title, date of publication, subsequent publications, character details etc.

So I’d like to state that Douglas Parmeé’s translations here are perfect. Of course, not being able to compare them with the French I can’t make a direct comparison, but they read beautifully and the translator is unobtrusive which is all that the general reader requires. My only gripe with Parmeé is with the story titles; he states that ‘Zola’s titles are often rather unenlightening, and the translator has ventured, here and there, to provide English versions that may be found more stimulating.’ So Naïs Micoulin becomes A Flash in the Pan, La Mort d’Olivier Bécaillé becomes Dead Men Tell No Tales and so on. Why do this? Why does a story title have to describe what happens in the story? Presumably the translator wouldn’t do this throughout the text so why do it with the title? This sort of thing tends to annoy me but it is the only gripe I had with the book.

The stories are roughly in chronological order and so the first five are quite early ones; they’re quite playful and in a way, quite modern. In the four-page story, Death by Advertising, Zola describes a man who tries to live his life by trying every gadget and product that is advertised and to believe faithfully the claims that the advertisers make – it doesn’t end well! In Rentafoil we hear about Durandeau who has found a market for ugliness; he sets up an escort agency whereby women can rent an ugly companion so that they look beautiful in comparison. The last story in the collection, The Haunted House is a sort of anti-ghost story; it’s amusing but it’s a bit of a ‘throwaway’ story.

Although these are quite fun to read, it’s the rest of the stories that really impress. There’s quite a range as well; a range in styles and settings. For example in two of the stories, The Way People Die and Priests and Sinners, the stories are made up of small sketches. The Way People Die starts off describing the lavish funeral of the Comte de Verteuil, then the successive funerals of a judge, a shop-owner’s wife, the sickly child of a washerwoman and bricklayer, right down to the seventy year-old peasant Jean-Louis Lacour. In Priests and Sinners Zola goes the other way, from poor to rich; he starts off with a parish priest in a small village, who ‘looked like a peasant in his smock’, then we get Father Michelin, a confessor to several aristocratic ladies, right up to a soon-to-be cardinal busy writing theological articles.

The title story, The Attack on the Mill takes place during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, and the whole story takes place in and around Merlier’s mill and shows the effects of war on civilians. Running through the story is quite a typical nineteenth century love story, where Françoise is forced to decide whether her father or her lover lives. This story was Zola’s contribution to the Naturalist’s anti-war story collection, Les Soirées de Médan which also included Maupassant’s Boule de Suif.

Captain Burle tells the story of a womanising, gambling Charles Burle, who’s a regimental paymaster who can’t keep his hands off women and can’t stop stealing from the army to pay for his vices. His colleague, Laguitte, eventually gets tired of covering for him and decides to take action.

A Flash in the Pan takes place in Aix-en-Provence and a smaller seaside town. It centers on the love between the lazy son of a lawyer, Frédéric, and the daughter of one of their tenants, Naïs. The set-up seems quite uninspiring, but with Zola’s excellent characters and his descriptive skills he turns this into a wonderful story, with comedy, thwarted murder attempts and a cynical ending.

Dead Men Tell No Tales starts off with this sentence: ‘I died on a Saturday morning at six a.m., after an illness lasting three days.’ The narrator is assumed dead but he is still conscious. Ok, we’re into Poe territory here with a ‘live burial’, but it’s filtered through Zola’s brain. So, either he really dies in the coffin or he escapes and returns to his wife, right?

Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder starts off in the Paris Commune and concentrates on Jacques Damour, who gets involved in fighting and politics and ends up getting arrested and deported. He’s given up for dead back at home and his wife eventually re-marries. After several years he finds his way back to Paris and tries to see his wife. But what should he do? How will it end?

In my opinion, the best three stories are Coqueville on the Spree, Shellfish for Monsieur Chabre and Fair Exchange. When reading these stories the reader almost knows how it’s going to end right from the first page. The pleasure in reading them, therefore, centers on how Zola is going to get us to the end, rather than what is going to happen. In the introduction Parmeé makes this point: ‘it is not so much what is going to happen, as when and how is what we can expect to happen actually going to happen. Far less common is the question why something happens.’

Fair Exchange initially takes place in a small town and Zola introduces us to Ferdinand Sourdis, an amateur artist, and Adèle, the daughter of a shop-owner dealing in artist’s supplies. Adèle also paints. After the death of her father, Adèle and Ferdinand marry and move to Paris where Ferdinand has an initial success with one of his paintings. He enjoys his success but finds it increasingly difficult to produce more work; he relies on Adèle more and more as she organises his life and assists in his work.

Coqueville on the Spree is an unusual story by Zola in that it’s a lot of fun and there’s even a happy ending – there I’ve spoilt it for you! The story is basically simple: Coqueville is an isolated seaside village, and there are two rival clans, the Mahés and the Floches. They argue over everything. One day, following a storm, some barrels of liqueurs are found at sea. More and more barrels are found and the inhabitants stop fishing each day and instead ‘harvest’ the sea of its booze. They end up having a big booze-up on the beach which ultimately brings the rival clans together. Maybe they should try this in the Middle-East.

Finally, there’s Shellfish for Monsieur Chabre which is probably my favourite of the lot. Right from the character descriptions on the first page you can guess what’s going to happen. So it involves the forty-five year old M. Chabre who ‘had one great sorrow: he was childless’ and his beautiful twenty-two year old wife of four years, Estelle. The family doctor suggests that they should go on holiday to the sea and that M. Chabre should eat loads of shellfish. They meet up with the good-looking Hector who ends up joining them on some of their excursions. Both Hector and Estelle love swimming but Chabre can’t swim. So, anyway, Chabre eats loads of shellfish, Estelle and Hector go swimming and Estelle gives birth to a baby boy back in Paris. It’s the journey to the end of the story that’s brilliant, not the ending itself.

Oooh – I have this on Mount TBR – and now want to read it instantly!!

LikeLike

You won’t be disappointed if you do…honest!

LikeLike

Hey Jonathan, do you have any idea whether Zola’s short story La petit village was ever translated into English and what the translated title might be? Thanks!

LikeLike

Hi Mathieu. There is a story called ‘The Little Village’ in the ‘New Stories for Ninon’. Have you read it in French?

LikeLike

Thanks! I was reading the German translation yesterday, but would like to quote a passage in English. At least I know it exists now.

LikeLike